Restoring Wilderness to Connecticut’s Central Valley.

One of the most unique characteristics of the Central Lowlands of Connecticut is the traprock ridge that runs from Long Island Sound to Massachusetts. Ranging to over one thousand feet above sea level in Meriden, the “Metacomet Ridge” contains some of the last wilderness areas in Central Connecticut, and has been designated as critical habitat by the Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). For the most part, the Ridge has escaped development due to its steep slopes, rugged faces, and aquifer recharge function. However, as open space in towns and cities along the Ridge disappears, the Ridge has become a target for various economic interests, including quarrying for construction materials.

The problem of dwindling wilderness is global in scale. We are all familiar with the international outcry against the destruction of the tropical rainforests and the concurrent loss of biodiversity; yet we fail to consider the loss of the temperate forest that is occurring in our midst. Only a few centuries ago, the Eastern Forest harbored a diverse plant and animal community, with moose and elk, wolves and wolverines, cougar, lynx, and bobcat. The early settlers began the sequence of destruction, clearing the land for farming and timber, catalyzing the division of the expansive forest into fragments that today are nothing more than remnants of true wilderness with few of its original inhabitants.

Even though there is now more forested land than 100 years ago, the presence of a forest is not necessarily analogous to a healthy, native ecosystem (Biltonen, 1992). What is required is the restoration of the native plant and animal community that existed prior to the advent of our forbears.

This plan represents a biologically-viable framework to unite land owners, municipalities, and concerned citizens to work towards the restoration of wilderness in the Central Lowlands of Connecticut.

Wilderness in Central Connecticut?

Webster defines wilderness as “an area essentially undisturbed by human activity together with its naturally developed life community.” Pioneering Conservationist Aldo Leopold (1949) called wilderness a “base-datum of normality, a picture of how healthy land maintains itself as an organism.” In heavily-populated Central Connecticut, a casual observer would most-likely surmise that there is no wilderness in the region. However, the traprock ridge, “green and forested strips of wild land that bisect the heavily-developed Central Valley” (Bell, 1985), is an obvious candidate for wilderness recovery in the area. Large semi-contiguous tracts along the ridge currently exist in Meriden, Southington, Berlin, New Britain, and Plainville. Within each of these tracts lie many different types of ecosystems.

An ecosystem is the community of microorganisms, plants, animals, and their physical environment interconnected by an intricate web of relationships (Erlich, et.al., 1970). There are many communities along and within the traprock range: hilltop, midslope, and low slope oak forests; hemlock and beech forests; exposed ledge, talus, and rock ravine communities; wooded and shrub swamps; marshes; stream and stream bank communities; and man-made lakes (Jorgenson, 1978). The physical and biological diversity within this area is the product of millions of years of geological and evolutionary activity. Local biodiversity is enhanced by the topography of the area: rapid elevation changes, ravines, and various slope exposures provide habitat for many organisms living at the northern or southern extreme of their normal distribution. For these reasons, the Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection has designated the traprock range as a “critical habitat” and cites over twenty rare, threatened, or endangered species that may exist in the area (Dowhan and Craig, 1976).

Wilderness Destruction

A diverse biological community has the ability to resist environmental perturbations because of the existence of different species whose roles in the system overlap (Odum, 1971). When this diversity is reduced, the ecosystem becomes unstable and functionally unreliable. Furthermore, a reduction in biodiversity is accompanied by a contraction of the gene pool, which slows or stops the natural evolutionary process and impinges on a particular species’ ability to adapt to the environmental change.

Wilcox and Murphy (1985) stated that “habitat fragmentation is the most serious threat to biological diversity and is the primary cause of the current extinction crisis.” When a habitat is fragmented, the resultant communities become genetically isolated with concurrent loss of variation and resilience. Human-induced fragmentation creates unnatural habitat boundaries which allow opportunistic non-native species to interact with native species; this triggers a cascade effect of increased competition, susceptibility to parasitism, vulnerability, displacement, and loss. For example, the brown-headed cowbird (a non-native but local species) prefers fragmented and open landscapes and lays its eggs in the nests of native songbirds, causing a sharp reduction in juvenile songbird populations within 100 meters of openings (Brittingham and Temple, 1983). By preserving core wilderness areas, parasite populations may be minimized and native songbird populations salvaged.

The structure (natural composition, diversity, and relative abundance), function (natural flows and cycles), and integrity (quality based on structure and function: naturalness) of ecosystems must be ensured through preservation and restoration (Noss, 1991a). Harmonic wilderness can only be ensured by halting fragmentation and development and through the establishment of wilderness corridors that allow the unimpeded transfer of genetic material across the region. Wilderness areas and corridors would serve as genetic reservoirs from which remnant external populations could draw genetic material and thus be saved from extinction.

The State of Connecticut Council on Environmental Quality (Council on Environmental Quality, Connecticut Environment Review, 1991) has identified habitat fragmentation as the “single greatest factor” in the reduction of the quality of Connecticut’s wilderness and proactively supports local efforts to establish corridors to stem the rising tide of wilderness loss.

The Traprock Wilderness Recovery Strategy

The Traprock Wilderness Recovery Strategy (TWRS) is an ecosystem preservation plan designed to maintain and increase local biodiversity through the creation of the Traprock Wilderness/Evolutionary Preserve System. It is the local component of a project to create an interconnected network of restored wilderness in the East. This proposal endeavors to gain the preservation of the ridge in perpetuity through preservation commitments from land owners, stewards, and government agencies.

The TRWS consists of three phases:

Phase 1: IDENTIFY. This phase includes preliminary field reconnaissance, mapping (including Geographical Information Systems (GIS) work), and presentation of the plan to local and state officials and land stewards. Significant revision of the plan based on regional feedback will occur in Phase 1.

Phase 2: CONSERVE. This phase includes the preparation of legal documents to secure preservation of the region; physical posting of the core and inner/outer buffer zones; and efforts to ensure the integrity of the preserve (preventing ATV access, illegal hunting, etc.).

Phase 3: DEFEND. The final phase involves the ongoing effort to maintain the preserve; recruitment of new landholders into the project to expand the area of the preserve; the restoration of extirpated species via natural migration; and the elimination of non-native species.

While the proposed TW/EP is smaller in area than most wilderness restoration projects, it meets many of the wilderness restoration criteria as suggested by Noss (1991b), such as repeated intervals of habitat types to include climatic, topographic, and population-dynamic variations and intersite linkage of small areas into a functional network. A. Starker Leopold (1969) provided the land ethic foundation when he said that “each unit…should be viewed as an independent microcosm with many biological features and values of its own, all of which should be appreciated and sustained in some harmonious combination.” Every piece of preserved and restored wilderness contributes to the preservation of evolutionary integrity.

The Preserve Matrix: Cores, Buffers, and Corridors

The Traprock Wilderness Recovery Strategy employs the Multiple Use Model (MUM) developed by Reed Noss and L.F. Harris (1986) as a management tool. The MUM consists of core regions managed for native biodiversity, surrounded by buffer zones, and connected by wilderness corridors. In preserves with multiple separate core areas, intercore corridors are established to provide core connectivity. Core areas within a given preserve would be located in relatively remote areas, away from development, roads, and hiking trails. No ecosystem-altering activity (mining, roadbuilding, ORV use, new hiking trails, etc.) would be allowed within the core to allow for population and diversity rebound. A strong ecological community within the core would enhance surrounding biotic populations. Buffers serve to isolate the core from the intensively used land surrounding the preserve and provide supplemental habitat for native species inhabiting the core. Inner buffer zones surround the core, and allow for limited use such as hiking, cross-country skiing, and birding. Outer buffer zones allow for heavier recreational use, light road use, biologically-viable silviculture, and attenuation of adverse edge effects. Wilderness corridors provide dwelling habitat as extensions of reserves; provide for seasonal movement of wildlife and the dispersal and genetic interchange between core reserves; and allow for latitudinal and elevational range shifts with climatic change.

TWRS preserve design was based on a number of criteria, including road and utility line locations, topography, and historical land use patterns. Due to the relatively small overall preserve size, designated core zones include no roads, trails, or power and gas lines. Inner and outer buffer design was based on perimeter condition, historical land use evidence, and ledge location.

Corridors along the TW/EP vary from excellent to marginal. Overall, the regional interstate highway system delineates the northern and southern boundaries of the project. Interpreserve corridor design was based on topographic and historical use data (low-use roadways and boundary characteristics). Coreless preserves such as South Mountain function as major corridors linking the largest preserves. Long linear corridors (i.e., Cathole Mountain) and discontinuous tracts of undeveloped land adjacent to the preserves provide supplemental dwelling habitat, facilitate wildlife egress and ingress, and prevent adverse land use around the preserve.

The TW/EP System – Component Preserves

The TWRS encompasses five preserves: South Mountain, East Peak/West Peak, Short Mountain, Ragged Mountain, and Bradley Mountain. Most of the preserves contain glacially-exposed faces, outcrops, and ravines which contribute to habitat variety and microclimatic diversity. While the entire system functions as a corridor, a preserve generally consists of core, buffer, and corridor zones. Furthermore, a number of significant adjunct tracts have been identified that have been included in the plan.

Unifying the System: The Challenge

The TWRS is a first step towards saving the remnant wilderness areas in the Central Valley. Since the plan does not include land acquisition, its success will be wholly dependent on the landowners, land stewards, municipalities, and citizens of the region.

State agency support for projects such as the TWRS can be found in the State Policies Plan for the Conservation and Development of Connecticut (Connecticut Office of Policy and Management, 1987), the Connecticut endangered species document (Dowhan and Craig, 1976), and in the Connecticut Council on Environmental Quality Report (Council on Environmental Quality, Connecticut Environment Review, 1991). However, new acquisition and preservation efforts by the State are limited due to financial constraints; only through local and regional citizen initiatives and state/local cooperatives will land such as the traprock ridges be preserved.

A significant area of land within the preserve system is owned by local water utilities. The preservation of land for water supply uses and wilderness are infinitely compatible, as “the purest untreated water comes from dense, unmanipulated forest” (New Britain Water Department Watershed Management Plan, 1990). From the municipal government perspective, the existence of a large regional wilderness area has many benefits, including aesthetic and quality-of-life value and citizen initiatives to curb illegal activites within the preserve. The authors of the Southington Master Plan for Development found that well over one-half of the residents they surveyed stated that the rural character of Southington was its greatest quality (Veri, 1990). Landowners within and around the preserve benefit through increased land values relative to land in developed areas (Small, 1990) and through the protection afforded their land by concerned citizens. A number of approaches to the establishment of the preserve are possible, including:

- An alliance of landowners and stewards who collectively modify their land deeds (via preservation easements) to ensure preservation in perpetuity;

- A cooperative effort between state and local agencies to jointly purchase land for preservation;

- Donations of land to local steward groups/land trusts;

- Creation of a citizen’s covenant, by which residents collectively contribute funds to purchase preserve space and become land stewards through a share system.

Given the complex ownership conditions present along the ridge, a combination of these approaches would be required. The traprock ridges of the Central Valley contain the last vestiges of wilderness in our region. Through cooperative initiatives such as the TWRS, we can preserve the wild places and their natural communities.

The Preserves:

South Mountain

- Acreage: 650 (Core: 200)

- Minimum elevation (MSL): 330′

- Maximum elevation (MSL): 767′

- Corridors: Cathole Pass (E); Meremere (W).

- Primary land stewards: Meriden Water Department; CFPA (Metacomet Trail).

- Significant habitats and threats: Habitats include a 300-foot southern escarpment, marshes, streams, and a lake (reservoir). Threats include a southeastern quarry and housing development in the northwest outer buffer zone. The western corridor crosses Reservoir Avenue, a tertiary day-use-only road.

East & West Peaks

- Acreage: 2300 (Core: 500)

- Minimum elevation (MSL): 200′

- Maximum elevation (MSL): 1024′

- Corridors: Meremere (E); Winter Wall (N).

- Primary land stewards: City of Meriden; private landowners; CF&PA; (Metacomet Trail).

- Significant habitats and threats: East Peak, West Peak, and South Mountain are collectively known as The Hanging Hills. Habitats within include numerous east, south, and west- facing escarpments; ravines; permanent and seasonal streams and ponds; Hog Swamp; Meremere Reservoir with a small hemlock-shrouded island; Hallmere reservoir; and a large plateau 100 feet below West Peak with 80-90 foot hemlocks. Threats include off-road-vehicle (ORV) use, vandalism, and development along the northern reaches of the preserve.

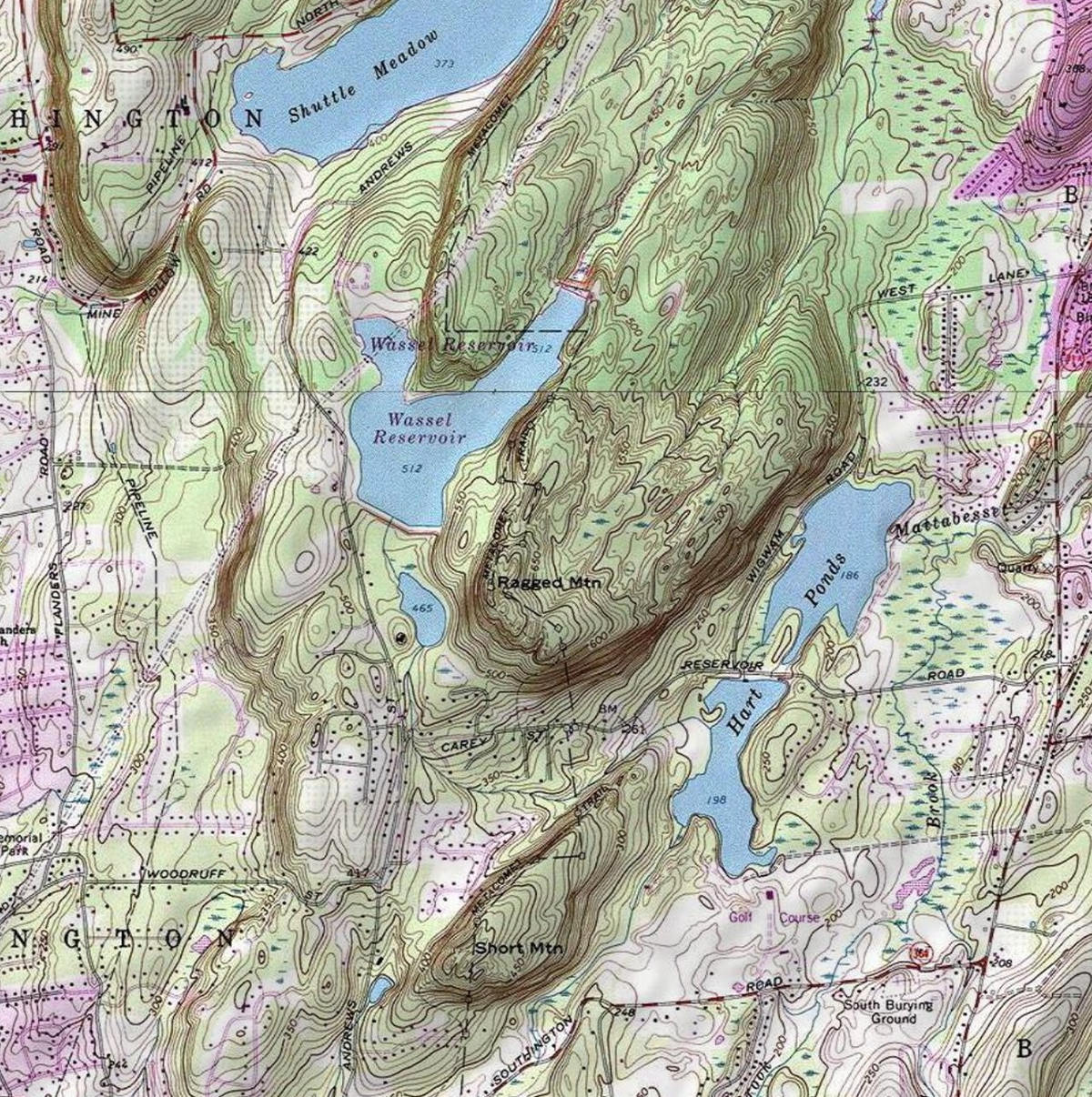

Short Mountain

- Acreage: 550

- Minimum elevation (MSL): 198′

- Maximum elevation (MSL): 520′

- Corridors: Winter Wall (S); Ragged Mountain Pass (N).

- Primary land stewards: New Britain Water Department; Town of Berlin; private landowners, CFPA (Metacomet Trail).

- Significant habitats and threats: Though the smallest of the preserves, Short Mountain includes hemlock ravines, numerous outcrops and precipices, and the South Hart Pond. Threats include development along the western outer margin.

Ragged Mountain

- Acreage: 2100 (Core: 700)

- Minimum elevation (MSL): 190′

- Maximum elevation (MSL): 760′

- Corridors: Ragged Mountain Pass (S); Shuttle Meadow (N).

- Primary land stewards: The Nature Conservancy/Ragged Mountain Foundation; private landowners; Town of Berlin; New Britain Water Department; CFPA (Metacomet Trail).

- Significant habitats and threats: The Ragged Mountain preserve includes the 600 foot-long western face that rises to 120 feet above ground level; dozens of ledges, outcrops, and ravines; three major lakes (reservoirs) and many swamps and marshes; a wildfowl preserve; and permanent and seasonal streams. Threats include ORV use, vandalism, and illegal hunting.

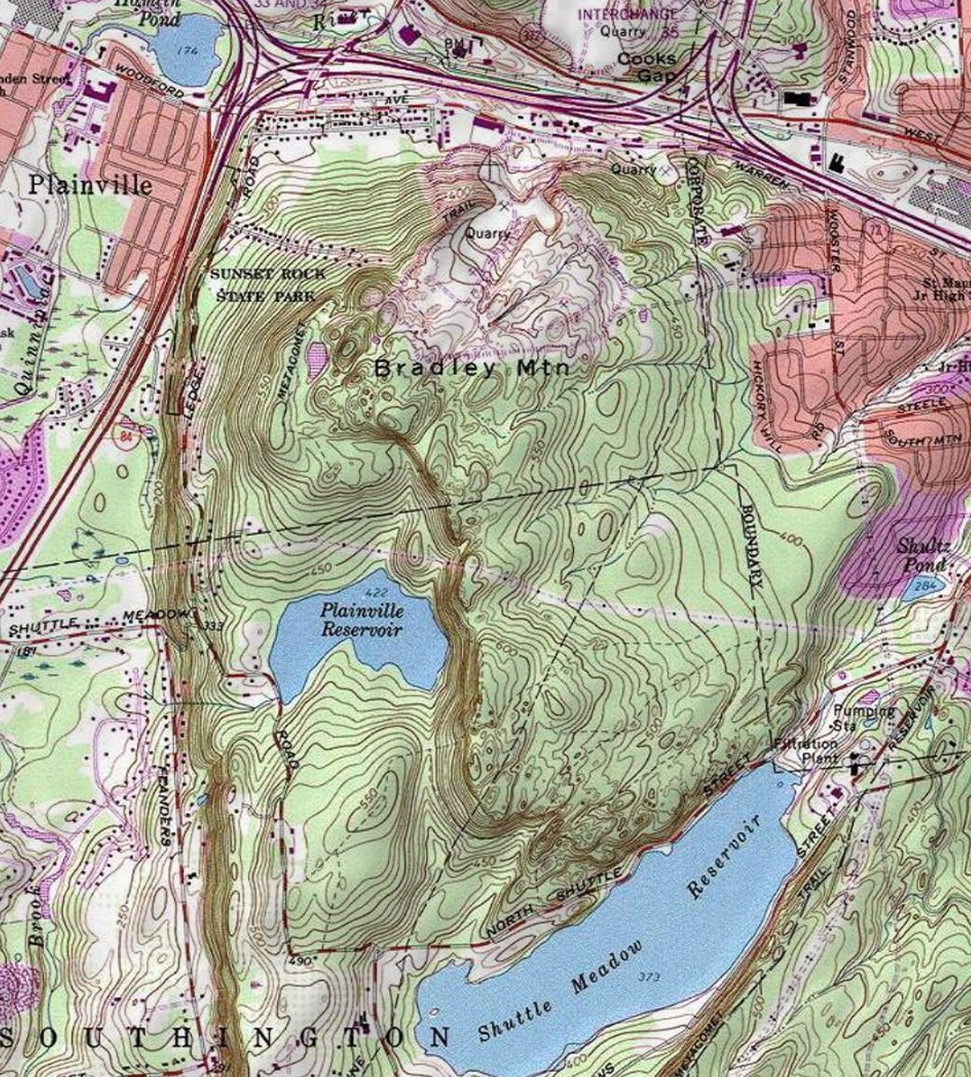

Bradley Mountain

- Acreage: 1500 (Core: 200)

- Minimum elevation (MSL): 300′

- Maximum elevation (MSL): 600′

- Corridors: Shuttle Meadow (S).

- Primary land stewards: New Britain Water Department; Plainville Water Department; State of Connecticut; Private landowners; CFPA (Metacomet Trail).

- Significant habitats and threats: The Bradley Mountain preserve includes Plainville Reservoir; remote outcrops and ravines; and Sunset Rock, an undeveloped State park. The major threat to this area is quarrying, especially in view of the substantial acreage owned by Tilcon and the potential expansion of the quarry. Other threats include illegal dumping and ORV use.

Adjunct Tracts:

- Cathole Mountain: Cathole Pass to Hatchery Brook. Threatened by mining and subsequent development.

- Penney Brook and Stocking Brook Watersheds

- Winter Wall, Ragged Mountain Pass, Shuttle Meadow

Author’s Note: Please do contact me if you are interested or working to protect the traprock range.

Literature Cited and References

Allendorf, Fred. W., and Robb F. Leary. 1986. Heterozygosity and fitness in natural populations of animals. In Conservation Biology: The Science of Scarcity and Diversity, Michael E. Soule (ed.). Sunderland, Mass.: Sinauer Associates. p.57-76.

Bell, Michael. 1985. The Face of Connecticut. Bulletin 110. Hartford: State Geological and Natural History Survey of Connecticut. p.100.

Biltonen, Michael A. 1992. The Finger Lakes Wilderness Recovery Strategy. Finger Lakes Wild!, Ithaca, NY.

Brittingham M., and S. Temple. 1983. Have cowbirds caused forest songbirds to decline? BioScience 33 (1):31-35.

Connecticut Office of Policy and Management. 1987. State Policies Plan for the Conservation and Development of Connecticut 1987-1992. Hartford: Connecticut OPM.

Council on Environmental Quality. 1991. Connecticut Environment Review. Hartford: Connecticut Council on Environmental Quality.

Corbett, Jim. 1991. Goatwalking. New York: Viking.

Dowhan, Joseph J., and Robert J. Craig. 1976. Rare and Endangered Species of Connecticut and Their Habitats. Report of Investigations Number 6. Hartford: State Geological and Natural History Survey of Connecticut.

Ehrlich, Paul R., and Anne H. Ehrlich. 1970. Population, Resources, and Environment. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. P. 157.

Hickey, Joseph. CT Department of Environmental Protection. 1992. Personal communication.

Jorgenson, Neil. 1978. A Sierra Club Naturalist’s Guide to Southern New England. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books.

Leopold, Aldo. 1949. A Sand County Almanac. New York: Oxford University Press.

Leopold, A. Starker, et.al. 1969. Reports of the Special Advisory Committee on Wildlife Management for the Secretary of the Interior. Washington, D.C.: Wildlife Management Institute.

New Britain Water Department, 1990. Watershed Forest Management Plan (Shuttle Meadow, Wasel, and Hart Ponds Reservoir Properties) 1990-2000. New Britain: New Britain Board of Water Commissioners. P. 14.

Noss, Reed F. 1991a. Ecosystem restoration. Wild Earth 1(1):18-23.

Noss, Reed F. 1991b. What can wilderness do for biodiversity? Wild Earth 1(2):51-56.

Noss, Reed F., and L.D. Harris. 1986. Nodes, networks, and MUMS: preserving diversity at all scales. Environmental Management 10:299-309.

Odum, E.P. 1971. Fundamentals of Ecology. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company.

Small, Stephen. 1990. Preserving Family Lands: A Legal Guide. Self-Published.

Veri, Albert. 1991. Town of Southington Master Plan of Development. Southington, CT: Planning Office.

Wilcox, Bruce A., and D.D. Murphy. 1985. Conservation strategy: the effects of fragmentation on extinction. American Naturalist 125. P. 879-887.

Last update: August 7, 2017