I’ve had a lifelong interest in trees, and conifers in particular, and have over 300 plants of many different species or varieties of conifers growing in containers. Most are dwarf or miniature varieties with a few cultivated as bonsai. I also collect alpines, heathers, and select deciduous trees including Boyd’s willows (Salix boydii). One of the biggest challenges in this endeavor, especially because it is container culture, is overwintering. Safely maintaining their winter dormancy is key to their survival.

Here in the southern Berkshires, we are in USDA Growing Zone 5a and we also live in a ravine with extended cold drainage periods. Most of my dwarf and miniature conifers (Zones 3 and up) spend the winter in cold frames or makeshift poly houses. Most of the more cold-tolerant trees (Zones 1 and 2, occasionally Zone 3) are kept outside on my growing porch. These containers are placed in cedar boxes and mulched in with shredded cedar bark. The largest container trees, reaching to 6′ in height, are kept clustered in a windbreak area and in direct contact with earth.

Since my soil type is riverwash (we live along a mountain stream), I was only able to sink the cold frames about 4 inches into the ground. The frames abut the north side of the house. I mulched all around the frames to about 6 to 8 inches above ground and added four intact bags of mulch side by side along the front and one on each side. Each cold frame has a heating pad on the bottom, atop an inch of cedar mulch laid in as a basement material. There is about 4 to 5 inches of mulch on top of the pads. I added mulch to cover the plant pots as I added them to the frames. The entire assembly is underlain with 1/4″-pitch hardware cloth turned up around the outside edges of the frames to prevent rodent incursion.

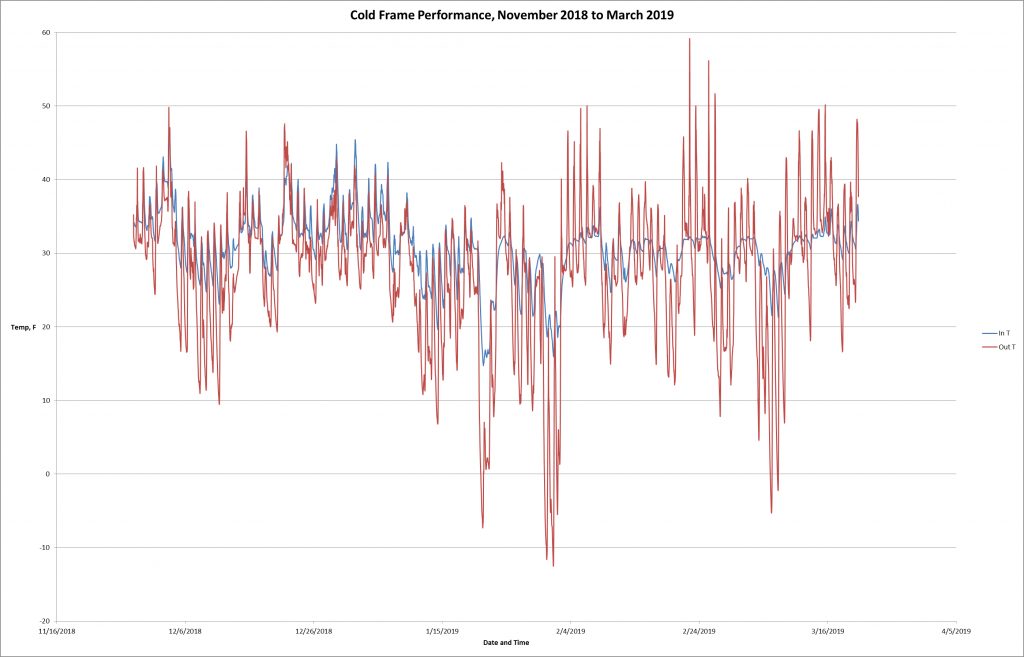

I use thermostatically controlled greenhouse heating pads to keep the coldframe mulch temp above 15degF. The pads only turn on when the mulch temperature drops below 15degF and they turn off once the temperature climbs back above 15degF. The system works well though it is uncommon for the cold frame mulch to get down to that temperature and trigger the heaters. It only happened once in winter 2018-2019 when air temperature descended to -14degF. Even then, it only cycled a couple of times during that night. On this graph, red is outdoor temperature and blue is cold frame temperature:

I often draw on the bonsai community to learn the fine points of applied conifer culture. A good rule of thumb in determining winter survival of container-grown plants is to add two zones to your USDA Growing Zone and work accordingly. I can winter-treat a Zone 3 plant like it is a Zone 5 plant and since I live in Zone 5, it’s good to go. Contrarily, a Zone 5 plant in container culture needs to be treated like it is a Zone 7 plant, meaning that I have to augment protection to ensure survival and requisite dormancy in Zone 5 conditions. And so on.

In the bonsai world, there appear to be two general cold-temperature thresholds of importance in overwintering temperate plants. The first is ~23degF when immature root mortality occurs and the second is around ~10degF when mature root mortality can occur. Such temperatures are not found at fine root depth in trees growing in the ground but are certainly possible in container culture. There is obviously only a relatively small soil mass with comparatively low thermal inertia in a pot as compared to that of the ground. So unprotected container plants are subjected to wide temperature fluctuations and freeze-thaw cycles unlike their naturally grown counterparts. The above-ground portion of the plants is as expected more robust than the root systems that require the protection/stability of the good earth. However, once new growth starts in early spring, the buds are easily killed if the ambient temperature drops below about 28 degF. So you have to be especially vigilant for late winter/early spring freezes affecting plants released from winter storage.

Strategies to improve winter survival include cold frames, unheated garage or basement storage, polyhouses, putting the containers in contact with the ground, mulching the entire pot up to the base of the lowest needles, and adding wind protection to reduce needle water losses on plants with frozen roots that cannot replace such losses. Wrapping a tree directly in burlap is not good for the trees (bud abrasion is a particular risk) but burlap is excellent when used as a wind break. I use 5′ high burlap on the fenced north side of my large-container conifer area and I also string it between the posts on the east and west sides of my south-facing growing porch where I keep my Zone 3 and lower containers in their winter cedar boxes.

I use Jewel Biostar 1500 cold frames for my smallest conifer work. They measure 59″ long, 32″ deep, and 16″ high (rear height). They are German-engineered and fabricated and I’ve found nothing better in quality well beyond their price. They consist of panels of twin-walled polycarbonate in an aluminum frame. There are three top panes. They come with a paraffin-driven automatic pane opener on one of the three panes for temperature regulation that is only of use during the warm growing season. They are durable but light and they can easily be moved to another location. We use them to grow conifers from seed once we liberate the winter residents from their quarters.

My primary concern in winter is moisture buildup in the cold frames where 100% humidity and unusually warm winter temperatures may lead to problems with pests, fungi, or molds. I have been venting the frames on the warmest winter days. I’m still not solid on the subject of watering plants during the winter, since the conventional thinking is to not water frozen plants. The idea is to water them thoroughly just before the big freeze (not an easy task with such variable weather during the fall-winter transition). Mulch and big humidity in the cold frames certainly help retain soil moisture in the containers. Outdoor plants get a helping of snow added around and atop the containers so that water is available when they thaw, and to reduce whatever moisture transpires/evaporates from a bare frozen-soil surface.

For my outdoor plants, the largest container plants get exposed to natural winter rains and snow so I don’t worry about them in that regard. They are prepared for winter by keeping the containers in contact with the earth, mulching 6″ to 10″ around the outside bottom of their pots, adding a thick layer of mulch to the tops of the pots, and, as mentioned above, by erecting a 5′ high burlap windscreen to prevailing windward. Pot type matters as well, with thick pots adding thermal inertia to the soil body. I have two Juniperus chinensis ‘Kaizuka’ that are about 6′ tall that I particularly treasure. They are Zone 4a trees and I am growing them in rugged, glazed earthen pots with 2″ thick walls to help them through the winters. The pots themselves have not shown the typical cracking of thinner or unglazed pots that happens because of freeze-related expansion of the water in their pores.

I also put some container-grown alpine flora in the cold frame and leave others out in the elements. I am experimenting with winter survival, pushing several alpine species in small containers into exposed locations to see if they can make it here without any winter augmentation. There will be more about alpines in a future post.

I used to bring my Japanese black pine (Pinus thunbergii) and Japanese white pine (Pinus pentyphylla) bonsai to Bonsai West in Littleton, MA for winter storage. For winter 2019-2020, I am storing in them in a makeshift poly house along with other larger conifers. This is an experiment to test the common theory. I have several ponderosa pines (Pinus ponderosa) that range in age from 35 to 90+ years old that I absolutely adore and they are kept outside in their bonsai pots that are sunk into the mulched cedar boxes. They were collected in the wild in South Dakota. They should continue to survive in the New England climate if the theory and collective wisdom are right but they did not show robust growth during the 2019 growing season.

Lastly, I use a couple of approaches to monitoring temperature and humidity in the cold frames and around my outdoor conifers. I use a SensorPush thermometer/hygrometer network that operates via Bluetooth to link to my iPad and iPhone. Sensors were installed inside of the cold frame and at the base of one of the large container plants, the latter to provide an outdoor reference. They provide fine-grained data that is exportable for analysis. I also use conventional mercury min-max recording thermometers outside and inside of the cold frames. You have to make sure that none of the thermometers see direct sun as they will deliver erroneous readings. Of course, this is all unnecessary but weather and meteorology are also obsessions of mine and I love interests with purposeful overlaps.

Happy overwintering!

—

Published 3 January 2019

Last update 12 November 2019

Hi Harry:

Thank you for the great advice on overwintering conifers. I am in Freeport, Maine zone 5b and have started a dwarf conifer business. Our approach is to grow in either terra-cotta or fiber pots. Of course the challenge is the overwintering to not only save the conifers but the terra-cotta pots. So far, so good. Most of my stock is Iseli dwarf conifers and I am maintaining in a small redwood/polycarbonate green house . I am keeping the inside temperature between 30-70 degrees and so far nothing has budded out. I do have a question though in regards to watering. Should I continue to occasionally water at these temperatures or keep them on the dry side until spring? I appreciate any advice and direction. Best Regards.