Land trusts protect a wide spectrum of lands, including natural and industrial forests, fields, wetlands, rivers and streams, shoreland, and farmlands. Protection begins with the actual acquisition, a tough place to start because most acquisitions are challenging to bring to closing for a variety of reasons. But once the property belongs to the trust, the real work of stewardship, the work in perpetuity, begins.

Stewardship in the land trust community quite frankly scares the hell out of me. Many are engaged in manipulations that are not grounded in good science. There are many great volunteers, board members, managers, and stewards out there, no doubt. But most trusts don’t have a science staffer, someone who understands that the forest is more than trees. And that is a problem or the root of many problems. Many trusts rely on board members or administrators to lead their stewardship programs and these folks often follow the grant money. There are lots of trusts that think that every preserve needs a trail “for the children” or that farmers always know best, or that forests need logging to keep them healthy. They rely on experts without understanding that their experts can bring biases that can degrade the preserves. They believe that state scientists know best without an understanding of what actually drives their agencies and programs (hint: it’s often not good science). They believe what their daddies believed without wondering if maybe there are better ideas. Or they get an itch about something in a preserve and they go and treat that itch without understanding the potential implications or unintended consequences of their actions.

Let’s talk about what I mean by “stewardship work” beyond treatments or trails or boundary monitoring. I mean taking the time to really think about what should or should not be done in a preserve. The fingerprint of what you do today may resonate over centuries. So caution is in order, deliberate thought is in order, and research is in order. Resist the edict or urge to knock off a management plan just to get it done. Rationalize and defend the need to observe and reflect on that place by being in that place many times before you decide what to do. Do your research, get in the journals, and read the papers. And when you write your plan, start from the highest level of defense of nature and natural processes, and if necessary, descend from there.

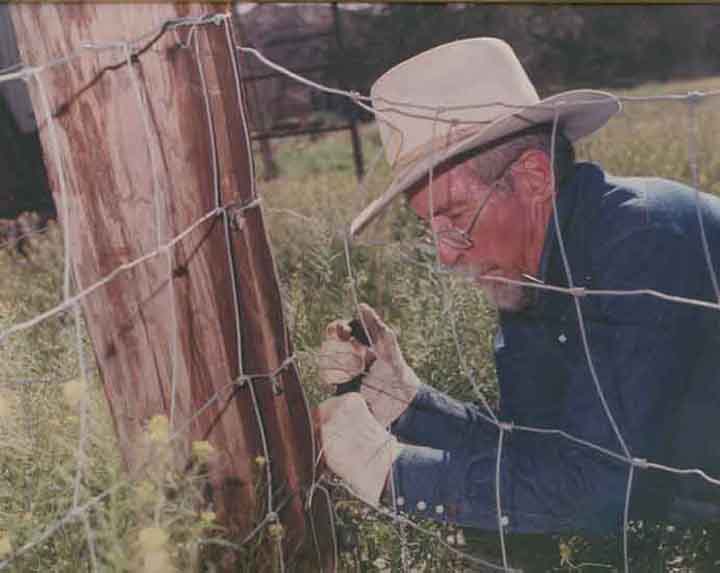

Jim Corbett (1933-2001) of southeast Arizona was a visionary in this realm. The Quaker son of Kentucky pioneers and the Blackfoot, he was deeply interested in the confluence of man and nature. In 1988, he started the Saguaro-Juniper Project that today protects over 10,000 acres and fosters both natural systems and agricultural practices on the block. Early on, Jim began goatwalking – wandering the preserve for weeks with only a few milk goats as his companions and some basic provisions in his pocket. As a philosopher (with a Harvard MA in Philosophy), Jim understood the need to absorb the essence of the land, to be in deep communion with a natural place, and to learn from it.

I had the great pleasure of hosting Jim during one of his stops on a speaking tour in 1991, the same year he published his best-known work, Goatwalking. I spent a couple of days with him and he stayed over at my undergrad apartment. He was an incredibly humble and kind person, brilliant almost beyond belief, and he had done more and different things in his life than most of us would imagine (professor, cowboy, ranger, refugee smuggler, prisoner, botanist, farmer, and more). He was the co-founder of the Sanctuary Movement where as a guide he learned the ways of the desert. But most importantly to the land trust community, he was a pioneer in the stewardship of the land.

From his immersive experiences in the natural world, the philosopher detailed a remarkable statement and a Bill of Rights for the Land that can serve as core values to guide our stewardship work:

From the Preamble to the Saguaro-Juniper Covenant (1991):

In acquiring governance of the land, we agree to cherish its earth, waters, plants, and animals in a way that promotes the health, stability, and diversity of the whole community. This entails attentive stillness to meet and know the land as an active presence. It entails study, observation, shared reflection, and cumulative experience to increase and bequeath our understanding of ecosystem health, stability, and diversity. It entails symbiotic naturalization into the land community – a communion of actual nurture and shelter. As elaborated by these entailments, fully accountable governance – stewardship – is the distinctly human way of bonding into one society with all who share in the land’s life.

THE SAGUARO-JUNIPER COVENANT PRINCIPLES

(A Bill of Rights for the Land)

- The land has a right to be free of human activity that accelerates erosion.

- Native plants and animals on the land have a right to life with a minimum of human disturbance.

- The land has the right to evolve its own character from its own elements without scarring from construction or the importation of foreign objects dominating the scene.

- The land has a preeminent right to the preservation of its unique and rare constituents and features.

- The land, its water, rocks, and minerals, its plants and animals, and their fruits and harvest have a right never to be rented, sold, extracted, or exported as mere commodities.

So what does this mean in practice? Let’s look at forestland since it is the most common cover type in New England land trust catalogs. Farming is a whole different world, and I’ll write about that in a separate post. But for the forest, the Bill of Rights for the Land dictates benign management, essentially benign neglect. It is explicit in its defense of native biodiversity and natural processes.

Here are some of the prohibitions that can be put in management plans that embody the Bill of Rights for the Land:

- No logging or other forest manipulation except for treatment of non-native invasives.

- No regular human access into designated core areas. Use drones to monitor.

- No hunting, shooting, poisoning, or trapping.

- Predators and wild herbivores are protected, even if they attack livestock or other domesticated animals or eat gardens or orchards, unless there is reason to believe they are rabid. Poisonous reptiles are protected. Beavers and their works are protected for their keystone ecological roles.

- The possession and use of firearms by caretakers for narrowly defined humane slaughter, critical ecological intervention, and for humane killing of sick or injured animals is excepted.

- No herbicides or pesticides except in treatment of non-native plants.

- No machines except in treatment of invasives and for aerial monitoring.

- No access for utility lines.

- No off-road motorized travel.

- No new roads.

- No use of heavy equipment to maintain existing roads.

My experience and research over two decades has shown that it is always best to begin the protection process – both in acquisition negotiation and in stewardship – from the place that fully protects nature and natural processes. Compromise happens, but start with an eye toward protecting everything. Be strong and be resistant, to the best of your ability, to anything less and go from there. Know your science and use it convincingly to defend the land.

Good luck in your conservation endeavors!

5 Nov 2017